Discover more from The Ecological Mind: ecology, research, creativity

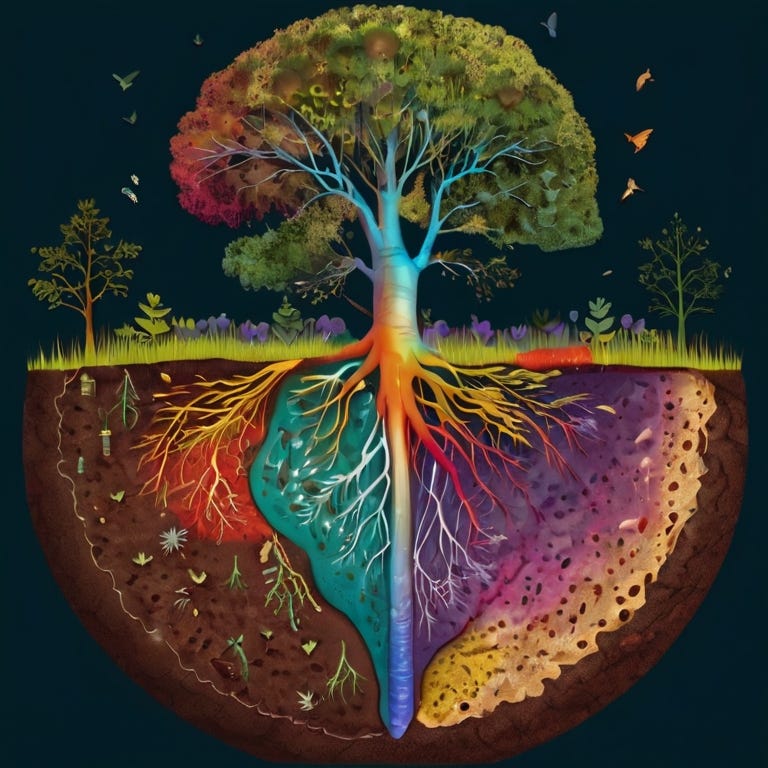

Soils, soil microbiome and 'mechanistic understanding'

Do you think we can ever really understand what's going on? and what does this even mean?

We recently had a rather interesting discussion in lab meeting, following discussion of a paper (a preprint) from the Seppe Kuehn lab. This paper proposed a relatively straightforward mathematical description of complex microbiome responses to pH in terms of what they did with nitrate. The work is quite impressive, because it appears to integrate across various different studies, reconciling some of the findings.

The discussion went a slightly different route, somewhat departing from a discussion of just the paper. For example, I was wondering if we can ever really understand what goes on in the soil, microbiome and all. My provocative statement was: we will never understand it fully. That was met with some opposition. And I think that’s good. Because if we can never really understand it fully, then what’s the point.

But this led to the question: what does it really mean to understand something fully. Is being able to describe outcomes with some equations understanding something fully, in terms of mechanistically. One of the occasions where it would be good to have our own resident philosopher of science, I suppose.

What does understanding something in this context mean for you? I think prediction is not enough, that seems clear, even though some people do equate prediction with understanding. That is wrong, because you could predict something correctly for the wrong reasons (this is at least what I think).

The reason this is such an interesting question for the soil and its microbiome is that we’re dealing with thousands genomes of just bacteria, but then there is so many other organisms, and so many physico-chemical aspects, so many processes, so many interactions. To me it seems beyond reach in the foreseeable future.

It seems there are different levels of what one could call “mechanistic understanding”. Describing a behavior with equations is certainly an amazing first step. But there’s much in terms of the underlying ecology that is then still not captured. For example, why do some microbial phylotypes increase and others decrease, what are the interactions underpinning such shifts? Or one could ask, what are the properties of some microbial taxa that allow them to perform well given environmental pressure ‘x’? How are these manifested in their genomes, etc? Or is that at some point irrelevant detail? Where is the proper cut-off for calling something ‘understood’, and does this even exist? Mechanism does reside at the level (or levels?) underneath the phenomenon observed, generally speaking. But where is understanding really reached?

It also seems clear that an ‘absolute’, ready-for-everything level of understanding is probably not feasible and maybe also not a worthwhile goal. It seems maybe mechanism is always provided with respect to a certain defined question or hypothesis, something much more specific. And that seems much more attainable.

Any opinions, or pertinent (accessible) literature would be greatly appreciated!

I love these questions so much. In grad school, our professor had us read Karl Popper’s article, “Limits to a scientific understanding of man,” which made a big impression on me. And in the film about the Large Hadron Collider, “Particle Fever,” one of the theoretical physicists had as his goal in life to discover (or develop) the one equation that explains the universe. I resist this reductivism. Your own example of the microbiome of soil points to the need for humility in the face of such complexity. And this post demonstrates the need for environmental humanities to pair with environmental science. We are a curious species, and our questions can come from many perspectives, including mathematics and philosophy.

Such great questions. Your term "understanding" is interesting in itself. If, for example, a friend is down with a problem and goes to you for sympathy because they know you are "understanding," it's not because you have a quantitative analysis of their problem, but because you are able to empathize. I would argue that this ability, to understand outside of quantitative certainties is essential for any true knowing. Indeed, I feel our capabilities for numerical analysis is hindering our ability to truly understand of where we are. We seem to be backsliding toward a Newtonian, mechanical view of the world.